Get 20% off forever by clicking the button below.

Yesterday, I kicked off my Free Agency article series. In the past, I have done this has one gigantic article, but splitting it up into three parts allows you to get more thorough information you can easily digest.

Free agency has always been my favorite part of the NFL offseason. This is why I have dedicated a lot of time and effort into learning the in’s and out’s of free agency. I still learn something new every year. I have built my particular area of expertise around this time of year.

One piece of advice for those that want to either learn or verify other people’s information: Use Spotrac.com. It’s the most user-friendly of the two salary cap web sites, and they lay out everything in a clean and clear format. Don’t listen to podcasts or Twitter users and just take their word on certain cap/contract topics (PK, TD, Mike, and Myself excluded), always double check.

Today, I am going to break down even further the different parts of a contract. I will do a quick redefining of the words we are covering today, but if you need to know the dates of Free Agency just click here. Quick refresher of what the article series will consist of:

Free Agency 101 (Yesterday)

Dates to Know

Free Agency Glossary

Salary Cap Basics

Franchise/Transition Tags

Free Agency 201 (Today)

AAV vs Cap Hit

Guaranteed Money

Signing Bonuses

Incentives

Dead Money

Cash Flow

Free Agency 301 (Tomorrow)

The Anatomy of a Contract

June 1st Designations

Restructuring vs Extending

Compensatory Picks

Contract Glossary

Guaranteed Money: The amount of guaranteed money a player can possibly earn over the course of a contract. This isn’t fully guaranteed money.

Fully Guaranteed Money: The amount of money in a contract that the team is responsible paying the player no matter what. This money is guaranteed at signing.

Roster Bonus: Compensation earned by remaining on a team's roster on a certain date.

Per-game Roster Bonus: A roster bonus awarded on a per-game basis for being on the team's game day roster or its active 53-man roster. Varies by contract.

Prorated Bonus: Typically, a signing bonus or Option bonus. This amount of money gets prorated evenly over the current and remaining years of a contract equally. When this bonus becomes active, it is paid upfront.

Incentives: Incentives fall into two categories: "likely to be earned" (LTBE) or "not likely to be earned" (NLTBE) based on the player or team's prior-year performance. Typically, LTBE incentives count against the team's salary cap in the current season, and NLTBE incentives do not count against a team's current year's cap. In rare cases, unearned LTBE incentives are credited to the following season's salary cap, while earned NLTBE incentives are charged against the following season's salary cap.

Dead Money: Refers to salary a team has already paid or has committed to paying (signing bonus, fully guaranteed base salaries, earned bonuses, etc.) but has not been charged against the salary cap. In business terms, it is essentially a "sunk cost."

AAV vs Cap Hit

Confusing AAV and cap hit is absolutely the most common error and mistake that happens on Twitter. Since I have started writing these article series, I feel we have made progress as a social media society in this area.

AAV is how much a player is paid per year over the course of a contract. It's simple math. Take the total amount of the contract and divide it by the years. Simple right?

AAV =/= Cap Hit.

Let me show you. Harold Landry has a 5-year, $87.5M contract. $87,500,000/5 years = $17.5M AAV. However, his cap hits are different. Here are his cap hits with his base salary and bonus monies in parenthesis:

2021: $5.05M ($1.25M + $3.8M)

2022: $18.8M ($15M + $3.8M)

2023: $21.05M ($17.25M + $3.8M)

2024: $21.3M ($17.5M + $3.8M)

2025: $21.3M ($17.5M + $3.8M)

See! AAV =/= Cap Hit!

You should never…I repeat…never, look at a tweet or article where it says a player is going to command $XXM a year and flip out immediately, because until you see the bonuses and guarantees, you don't really have any idea about the cap hit (unless it's a one-year contract, of course).

AAV is great for agents and players themselves to try and get paid more money. A perfect example was the wide receiver market last year. The Jaguars ended up paying a contract with a $18m AAV, and even though that was an absolutely insane thing to do, it let agents get more money for their young wide receivers. Agents for guys like Terry McLaurin, A.J. Brown, DK Metcalf, and Deebo Samuel all essentially used that as the jumping off point for negotiations.

Again, cap hit is totally separate. Cap hit is what the player actually gets paid that year plus any signing bonuses or incentives that could be from the current or previous season(s):

Base salary + certain incentives + signing bonus = cap hit

As we saw above, it's different from the AAV. Rest assured, with your Tennessee Titans, any contract will almost always have a much lower first-year cap hit compared to the AAV.

Cap hit is the most important thing, in my opinion, when it comes to looking at contracts. Before we head to the next section, let me say again: CAP HIT =/= AAV

Guaranteed Money

Guaranteed money has become the major sticking point for most, if not all, contract negotiations. The NFL rarely gives out massive, fully-guaranteed contracts. In fact, the most recent one has sent shockwaves that still have yet to be fully felt.

Last year, the Cleveland Browns went bonkers and gave a massive guaranteed contract to a quarterback who hadn’t played in over a year, had 20+ sexual assault allegations, and was suspended for a large chunk of 2022.

This contract had the NFLPA come out and try to leverage this dumb, disgusting use of money. They are now pushing for the NFL to remove an old archaic rule to get more players fully-guaranteed contracts.

The NFL owners don’t want to, and probably will never remove the rule (more on this later), and thus while you will see larger sums of fully-guaranteed money, you won’t see a lot of fully-guaranteed contracts.

There is a big distinction between guarantees and fully-guaranteed money. Normally, you will see a tweet or article saying the largest number first. That is typically said in a fashion of “Player X got a 5/yr $150m contract, with $100m guaranteed.” Sometimes it may say $100m in guarantees, but the point is no where in the tweet does it say that the money is fully-guaranteed.

Likely, that large number isn’t fully-guaranteed, though with every passing offseason it becomes more likely it will be close. You’ll usually get a second tweet explaining what portion of those guarantees are promised in full.

For the purposes of how I explain articles or will explain the difference we will call non-fully guaranteed money total guarantees, and denote the fully-guaranteed money as such.

Total Guarantees: This is the total amount of guaranteed money agreed to in a contract. Simply put: Fully Guaranteed Money at Signing + Guarantees Activated Later. Essentially, dates or certain milestones can trigger guarantees later. When those events are reached in the course of the contract, guarantees that were previously not fully-guaranteed

Fully-Guaranteed Money: This can also be known as money that is guaranteed at signing. This portion of the contract is mostly paid up front (signing bonuses), while the other amounts are kept in escrow and paid over time. Only in the rarest of instances would a player not receive his fully guaranteed money.

Let’s use a quick example of Von Miller’s contract. The Buffalo Bills paid him a 6yr/$120m contract. $45m was guaranteed at signing while total guarantees come in at $51.435m. Let’s break it down:

Fully Guaranteed

$18.525 (signing bonus)

$1.12m (2022 base salary)

$1.3m (2023 base salary)

$13.51 (2023 roster bonus)

$10.71m (portion of 2024 base salary)

Total Guarantees

$45m in Fully Guaranteed

Remaining $6.435m of 2024 salary becomes fully guaranteed in March 2024

So to reach those total guarantees, Miller will have to still be on the roster in 2024. It’s very likely he is, unless he is traded due to cap savings/dead money issues, but that illustrates the difference in how contracts are laid out and talked about.

Guaranteed money comes in all forms: Base salaries, signing bonuses, Roster Bonuses, incentives, option bonuses. So, sometimes it’s going to take a lot of digging to find out the truth. That is why I always preach patience when an initial announcement tweet goes out.

Bonuses

There are three different bonuses that I wanted to talk about today: Signing Bonus, Roster Bonus, and Option Bonus. I am throwing a lot at you today so I am going to try and keep this section simple.

Signing Bonus: The most common form of fully-guaranteed money. This a bonus paid to the player up front at signing. This is a fully-guaranteed bonus. because the signing bonus is such a large lump sum paid up front, to lessen the cap hit, teams are allowed to spread the amount evenly over the remaining years of the contract, up to five years. When that happens its referred to as prorating.

Roster Bonus: Is a bonus that can be fully-guaranteed up front or become fully-guaranteed later. This bonus kicks in when a player is on the roster by a set date agreed upon between him and the team in a contract. An example would be Aaron Rodgers current contract where the roster bonuses in 2025 and 2026 but aren’t fully-guaranteed yet:

2025 Roster Bonus: $5M (paid 4/15/2025)

2026 Roster Bonus: $5M (paid 4/15/2026)

Option Bonus: This is like a signing bonus, but triggered at a later date. When triggered it becomes fully guaranteed and it can be pro-rated over the length of the remaining contract for up to five years. This can either be a team-option or player-option. Which means that one of the entities has total control over whether or not to trigger the option.

Myles Garrett is a good example of option bonuses kicking in. He signed a 5yr/$125m contract back in 2020 and he had two option bonuses that kick in:

2021 Option Bonus: $20.665M (guaranteed, paid the 3rd league day of 2021, 3/19)

2022 Option Bonus: $17.965M (guarantees the 3rd league day of 2021, paid 3/19/2022)

You can see that 2020 is blank, and once the 2021 option bonus kicked in, he is paid that $20.665m in total on the due date, and it’s split over the next five years starting in 2021. that amount falls off by 2026 because of the five-year limit.

It grew in 2022 due to the second option bonus that kicked in. $17.965m paid on a due date in total, and split evenly out to through the remainder of the contract.

We aren’t to dead money or cash flow yet, but these option amounts get added into the dead money amount. Of course because they’re paid in total they have a direct effect on cash flow as well.

Incentives

The thing to know about incentives: not all incentives are created equally. There are actually two types of incentives to familiarize yourself with: LTBE and NLTBE.

LTBE: This stands for "Likely To Be Earned." These are incentives that are classified as something that will likely happen and thus will count against the salary cap.

NLTBE: You probably figured this out already, but this stands for "Not Likely To Be Earned." This means this incentive probably doesn't have a good chance of being paid to the player and won't count against the cap.

Both types of incentives are based on what the player was able to accomplish on the field in the previous season. If they accomplished the incentive, it's LTBE. If they didn't, it's NLTBE.

In a completely hypothetical scenario, let's say the Titans sign a two-year deal with Jakobi Meyers this year. Jacob was active for 14 games in the 2022 season. Let’s say the Titans give him a contract in which he gets incentives for every game he’s active. Let’s say $29.5k per game.

Well, because he was active for 14 games last year, then $413k of the incentive money count towards the cap hit. Here’s how the math works:

$29,500 x 14 games = $413,000 cap hit

$29,500 x 17 games = $501,500 can be earned

However, what happens if Meyers gets injured and misses 8 games in 2023. The team is credited those 8 games back in 2024. Being it was a two-year deal, those incentives would revert to NLTBE and not count against the cap in 2024.

There is another side to this, and that’s going from NLTBE to LTBE. Let’s talk Taylor Lewan. If Taylor Lewan’s current contract is thrown in the trash, and he signs for a new two-year deal with the Titans, the safest bet for the team is to use a NLTBE incentive of 11 games or more where Lewan is a starter. We will use 11 for this example.

Well, because Lewan only started 2 games in 2022, these incentives would not count against the cap hit in 2023. However, if he starts for 11 games in 2023, those NLTBE incentives become LTBE incentives in 2024, and the cap hit owed is charged in 2024.

Dead Money

The buzzword of the 2023 offseason has been dead money. Everyone is so concerned about this money specifically when it comes to Tannehill’s contract, but guess what you’re paying it either way.

Dead cap is a sunk cost. You are either paying it as part of the contract, or you cut/trade a player and gain cap relief, but still on the hook for that money.

Whatever remains of the fully guaranteed money in the player's contract when a team cuts or trades him, all combines to count against the current year's salary cap for the team. The only exception is if it is a cut designated post-June 1st or a trade that happens after June 1st. If it’s after June 1st, the dead cap can be split between the current and following year. (See: Titans cutting Julio Jones) I’ll dive into June 1st stuff tomorrow.

Let me give you a clearer example that I frequently use about dead money:

You buy a car and get a loan with the bank. You agree that you are fully guaranteeing 60 payments at 0% in the amount of $51,000. You make payments for about three years and decide to trade in the vehicle. The vehicle is worth $30,400, and remember you still owe $20,400 to the bank because it was fully guaranteed. So, that means you have $10k in positive equity.

That's exactly how dead money works in most cases. Teams will eat dead money because they’re gaining a considerable amount of positive equity in cap savings. this is why trading or releasing Tannehill is a viable option if the team wants to save money against the cap.

That gets added to the dead cap amount for 2022. While they will have $18.8m on the books in dead money, they gain $17.8m dollars in cap savings that can be used right now. They can eat the dead money, and it comes off the books next year.

Let’s bring back in Harold Landry’s contract, he's fully guaranteed $35.25 million dollars. That mean's no matter what, this team has to shoulder the burden of $35.25 million dollars. However, on 3/19/2023 his entire $17.25 million base salary guarantees.

So, what does all of that look like?

Starting Dead Cap: $35,250,000

Signing Bonus + 2022 salary + 2023 salary

What the Titans paid Landry in 2022

$1.25m base salary, $3.8m signing bonus = $5.05m total

2023 Starting Dead Cap:

$33.25m - $5.05m = $30.2m

2024 Salary Fully Guarantees 3/19/23:

$17.25m

2023 Dead Cap after 3/19/23:

$30.2m + $17.25m = $47.45m

What the Titans will pay Landry in 2023:

$15M base salary, $3.8M signing bonus = $18.8M total

2024 Dead Cap:

$47.45m - $18.8m = $28.65 million

What the Titans will pay Landry in 2024:

$17.25m base salary, $3.8M signing bonus = $21.05m total

2025 Dead Cap: $7.6m

Now, there is one year left on Landry’s contract (2026), but I wanted to stop right here. that $7.6m in dead cap for 2025 is what is left over from the signing bonus. That’s the pro-rated amounts of $3.8m and $3.8m.

So, if Landry were to be cut in 2025, it would be a dead cap of $7.6m, and in 2026 it would be $3.8m. This is important because these low amounts are typically when a team considers cutting, extending, or restructuring a deal.

Landry carries a cap hit of $21.3m in both 2025 and 2026. So, cutting him either of those years yields the Titans a massive amount of savings:

2025: $13.7m cap savings, $7.6m dead cap

2026: $17.5m cap savings, $3.8m dead cap

So, no matter what a team has paid in terms of salaries, incentives, and bonuses, as long as the signing bonus is still actively pro-rated, the team is on the hook for those amounts in terms of dead money.

Can dead money be traded? Yes and no. Future guaranteed dead money can be traded. Dead money that’s already been paid cannot.

So, let’s keep it simple. Base salaries are not paid up front. So, let’s go back to Von Miller.

Von Miller has $10.74m of the 2024 base salary fully guaranteed. Normally, cut or traded the team would be on the hook for that fully-guaranteed money. However, the 2011 CBA now allows for that base salary, because it hasn’t been paid, to be part of the transaction.

This means while the acquiring team doesn’t have to take on that money, they could negotiate to take on some or all of that unpaid fully-guaranteed base salary. Let me provide an example to try and make it clearer.

The Titans are close with the Bills to trading for Von Miller. They offer two final scenarios.

The Titans do not take on the unpaid guaranteed portion of the 2024 salary, but offer the Bills a 2nd round pick.

The Titans say they will take on the entire 2024 salary including the guaranteed unpaid portion, but the Bills have to settle for a 5th round pick.

That’s about as simple as I can make it. Any unpaid, fully-guaranteed money that counts as dead money, can be traded.

Cash Flow (Yearly Cash)

There is no cap on the amount of cash that a team can spend in one year. Only what their actual financials ion ownership. This is how cash flow is different than cap space.

First, lets talk yearly cash. Yearly cash is how much a team pays that year into either the player’s bank account or an escrow account. Typically, the first year of a contract you would see a large amount of yearly cash but a low amount in terms of cap hit.

For example, Harold Landry’s contract.

2022 Cap Hit: $5.05m

2022 Yearly Cash: $20.25m

$1.25m, base salary

$19m, signing bonus

Remember, signing bonuses are always paid to the player up front, so that is cash spent. Here’s the other thing to remember, and I talked about this in the Ryan Tannehill Vs… series, the league operates with an old archaic rule that uses an escrow account.

This is called “The Funding Rule”. This rule was established in the NFL’s prehistoric era where some owners or teams were cash strapped, and terms of contracts were not getting fulfilled. So, what are the parameters of the funding rule?

According to the NFL CBA, any fully-guaranteed money over $15 million must be put into an escrow account. Using the structure of Deshaun Watson's contract, the Browns will have to deposit $184M into escrow since the Browns are already above $15M. In some cases, however, this amount may be reduced to $172.5M, which is 75% of Watson's total contract compensation, depending on an interpretation of Article 26, Section 9 of the CBA.

Owners just hate the idea of fully-guaranteed contracts from a philosophical standpoint, so they’re in favor of keeping the funding rule, despite the NFLPA wanting it gone. Other owners, like the Titans, have a real problem with fully-guaranteed contracts from a cash flow standpoint.

The Titans ownership group are already liquidating assets in an effort to fund their share of the new stadium. So, depositing large amounts of cash from guaranteed contracts into an escrow account, provides cash flow obstacles.

So, this is often times why the more “cash rich” teams can get big named free agents and hoard them, while the Titans have to sort of be more judicial with their money and resources, specifically right now.

Resources For You

Preferred Salary Cap/Contract web site: Spotrac.com

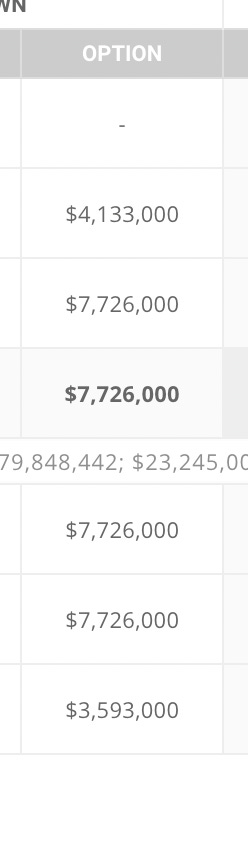

Franchise/Transition Tag Amounts (Projected)

Twitter Accounts: @spotrac, @Jason_OTC, @corryjoel

Don’t forget that if you’re not a paid subscriber, that you won’t have access coming up to the articles I put out Monday-Friday! So, click below to get started today!

You can also share Stacking The Inbox to anyone you may think will enjoy this comment! sharing is caring!